Key concepts

Relational Querying

Section titled “Relational Querying”SQL was first introduced in 1974 and unlike all other languages of its era it has remained completely dominant as the language for databases. SQL is also therefore by far the most well-known façade around the relational model. However unlike SQL---which rather understandably reflects its true age and evolutionary process through its many design flaws---the core of the relational model itself is a timeless manifestation of first-order predicate logic that predates SQL by 5 years (1969!). SQL’s undeniable success is because of the strength of the underlying model rather than (and perhaps in spite of) the façade.

SQL databases and other non-SQL (but ‘relational’) languages have routinely interpreted the relational model with unique twists and XTDB is no different in having a few opinions of its own (see below). XTDB 2.x is firmly grounded in the relational model and this is not only desirable but necessary for supporting SQL as a first-class language (complete with three-valued-logic and bag/multi-set semantics).

SQL is not the only game in town however. Datalog is the alternative query language that has long been supported by XTDB for constructing relational queries. Datalog is derived from the Prolog family of logic programming, and in contrast to SQL, emphasises composition using ‘rules’ and ‘unification’ (implicit JOINs). More crucially Datalog is amenable to being expressed as well-structured data and can therefore be trivially generated without resorting to any string interpolation headaches associated with building large SQL statements.

Instead of ‘Datalog’ XTDB v2 implements ‘XTQL’ - a novel relational querying language designed for composability whilst embracing the requirement for full interoperability with SQL. XTQL also incorporates key concepts from Datalog, and in particular retains the ability to ‘unify’ across relations using logic variables.

Schema-less & Dynamic Tables

Section titled “Schema-less & Dynamic Tables”Traditionally a SQL database requires an explicit schema to be designed and loaded ahead of time before any data can be inserted. Such a schema defines a static set of named tables, and for each table the columns must be ordered, named, and typed. The ordering of columns in a row-oriented database like Postgres carries significance, and schema migrations must account for this.

In contrast, XTDB is ‘schemaless’ and therefore does not require the developer to provide any upfront schema definitions before data can be inserted.

New tables can be asserted ‘on the fly’, and rows of data inserted into those tables are recorded alongside dynamic, self-describing type information based on a well-defined range of native types. XTDB does not possess any notion of column ordering for stored rows.

Included in the range of first-class types are composite types: sets, structs, maps, vectors. Composite types allow you to insert arbitrarily nested structures composed of types determined at runtime.

The striking implication of this design is that rich and deeply nested structures (e.g. JSON objects) can be effortlessly represented without normalization. This is reminiscent of the flexibility afforded by ‘document’ databases but doesn’t sacrifice SQL or relational algebra. It is also reminiscent of Postgres’ JSONB columns, however this approach maintains complete alignment with the relational query engine without introducing any additional internal or developer-facing complexity.

XTDB is not the first database to offer this level of support for dynamic data, but it is the first to do so with well-defined columnar data types via Apache Arrow. The flexibility of this approach is ideal for underpinning highly-normalized, graph-like data models.

Dynamic data is commonly found in the context of ‘data lakes’ where poorly-structured, messy data is expected. As a consequence, XTDB bears resemblance to systems like Databricks’ Delta Lake - also a columnar data architecture that “separates storage and compute” using commodity object storage. XTDB is a ‘Hybrid Transactional/Analytic Processing’ (HTAP) system which postulates that even organizations who don’t have Big Data problems (yet) can benefit from similar baseline capabilities, without having to introduce additional technologies alongside their transactional database system.

Records & Rows

Section titled “Records & Rows”XTDB is designed for making non-destructive updates to your data simple and achieves this by modeling row-level temporal versions of data. This works by representing each update as a new row that sits alongside the previous versions of that row in the same table.

However given that XTDB does not account for schema ahead of time, the only means of correlating updates to a row is to impose a single ubiquitous schema requirement: each row asserted must contain an explicit id column.

The value provided for the id column can be any of the supported ID types, but must be determined by the user.

XTDB does not offer a means of generating new IDs automatically although use of surrogate keys (e.g. UUIDs) is encouraged.

The ID allows a set of rows to be interpreted as the evolution of a single ‘record’, such that each row corresponds with a particular version of a record.

The id column together with the built-in temporal columns forms the default primary key for each table in XTDB.

Temporal Columns & Bitemporality

Section titled “Temporal Columns & Bitemporality”In addition to any user-defined columns asserted for a given row, XTDB maintains 4 built-in timestamp columns for each table.

These columns are:

_system_from_system_to_valid_from_valid_to

The columns are not visible unless explicitly queried. The values of these columns are maintained automatically and the respective pairs of columns always form ‘closed-open’ periods (i.e. inclusive of ‘from’, exclusive of ‘to’).

‘System time’ represents the audit history of all changes to records and captures the time that information entered the system. ‘Valid time’ is a user-managed dimension and can be used for a variety of purposes (out of order updates, backfilling data, domain modeling etc.).

system_time_start can be specified to allow for importing bitemporal records from legacy systems valid_time_from and valid_time_to can be specified to meet the requirements of the application design.

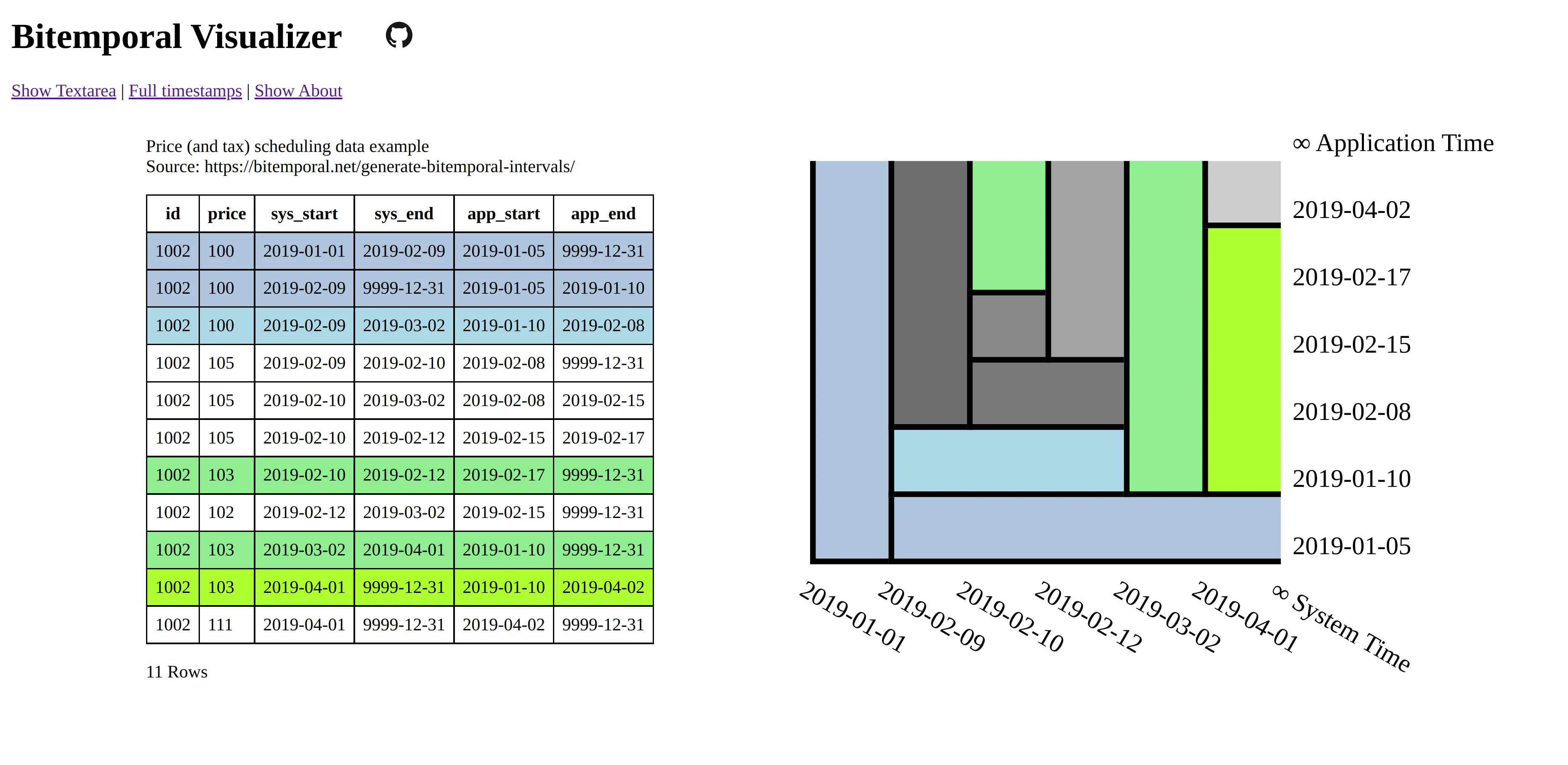

The combination of these columns is called ‘bitemporality’ and can be visualized in 2 dimensions. For example:

This definition of the bitemporal model was first defined by Richard Snodgrass and Christian Jensen as the “Bitemporal Conceptual Data Model” in 1994 and was (much) later adopted as the basis of the ISO SQL:2011 standard.

The bitemporal features defined in the SQL:2011 standard lack significant adoption and introduced many complexities for users. XTDB simplifies those features by making bitemporality ubiquitous and easy. For instance, XTDB maintains a built-in ‘WITHOUT OVERLAPS’ constraint which ensures that the ‘rectangles’ in this model never overlap, and also maintains a temporal index to accelerate various kinds of temporal queries (including the default ‘as of now’ query context).

Alongside a specialized temporal index, XTDB offers a set of temporal operators based on Allen interval algebra for understanding the intersections of bitemporal data (e.g. OVERLAPS, CONTAINS, PRECEDES).

The ability to model, reference and audit time-versioned records is useful across many domains. Application developers who are familiar with concepts like ‘soft deletes’, ‘event sourcing’, and ‘windowed joins’ will find a lot of relevant ideas and capabilities in the bitemporal design of XTDB.

Bitemporal modeling is commonly used across areas like data warehousing, stream analytics, finance and insurance. However most implementations are ad-hoc and challenging to scale.

Transaction Processing

Section titled “Transaction Processing”XTDB uses a single-writer architecture that ensures ACID consistency of updates regardless of the number of replica nodes used to scale read-only queries. The single-writer provides strong consistency guarantees needed for auditing and bitemporal timestamp generation. XTDB does not offer a sharded multi-writer architecture, meaning write latencies and availability are geographically sensitive.

Transaction logic is processed fully serially, deterministically and atomically on each node.

This means each transaction has exclusive access to the latest database state.

Beyond basic record-oriented operations (i.e. via INSERT & DELETE RECORDS), many complex transactions can be expressed declaratively via SQL transactions.

SQL transactions are non-interactive and mid-transaction writes are not queryable.

Foreign keys? Uniqueness constraints? Views? Indexes? etc.

Section titled “Foreign keys? Uniqueness constraints? Views? Indexes? etc.”XTDB currently has no native concept of Foreign Keys and therefore referential integrity must be implemented manually if it is desired, i.e. making sure the thing being referenced already exists in the database before you insert a reference to it, and conversely deleting all references to a thing when that thing is deleted. Referential integrity can still be achieved atomically, with ACID guarantees, either using ‘transaction functions’ or SQL.

XTDB has no concept of uniqueness beyond the ID. If you want something to be unique then you can and probably should model it with an ID.

Similarly, any other features of a SQL database that intuitively require a schema are not available within XTDB currently. It is however intended that XTDB will introduce “gradual schema” capabilities in the future to enable new usage patterns that includes using XTDB like a traditional SQL database (e.g. “just treat XTDB as if it were Postgres, and model your data the same way”).